Voices (Towards Other Institutions)

Editorial Project

For the past two years, the Russian Federation Pavilion in Venice has looked into the reconstruction of both its architectural and institutional structures. It is from the will to rebuild itself on better, more solid grounds within the new global order that this project stems.

In 2020, the Russian Pavilion was meant to stage the live, real-time reconstruction of the Pavilion’s building throughout the months of the Biennale. The temporary “settlers” in this Pavilion under reconstruction were supposed to be KASA – Kovaleva and Sato Architects (Aleksandra Kovaleva, Kei Sato), the young Russian-Japanese architecture firm that was selected following an open call with over 100 submissions to renovate the architecture and set up their temporary office inside the Pavilion. Through their gentle occupation of the exhibition space, the Russian Pavilion would activate a genuine space for engagement and discussion, both for the Biennale visitors and inhabitants of the Venetian lagoon alike.

In parallel, the architectural reconstruction of the Pavilion would trigger a broader reflection on the reconstruction of pavilions as institutions, and more in general on the meaning, the public role, the social function and the civic responsibilities of cultural institutions, within and beyond the Venice Biennale.

The original vision for the 2020 Russian Pavilion was thus one rooted in physical proximity as an ideal premise for sharing, learning and cari ng for each other. Yet with the outbreak of Covid-19 and the subsequent postponement of the 2020 Biennale, the need for another model of coexisten began to emerge…

In May 2020, the Russian Pavilion migrated entirely online, organically morphing into a digital platform called Open? (pavilionrus.com). In this way, the restrictions imposed by the pandemic became an opportunity to experiment with digital environments – the only ones that could be accessed at that time. From the confines of our homes, working remotely, scattered in different countries, we felt the need to reach out to one another and expand the boundaries of our conversation, rather than letting it shrink. For over a year, the digital platform Open? has served as a journal for new contents and collaborations, while also building up an archive for Biennales to come.

Striving to live up to the expectations the Russian Pavilion had set for itself – that of effectively functioning as a more porous, inclusive, critical and self-critical cultural institution – Open? shaped up gradually, over time. Throughout the past, difficult months, it has continued to systematically interrogate itself, and eventually has come about as the product of a collective effort to curate and care for a “living object”. What was meant to be a physical space for encounters gradually became a virtual gathering venue for multiple communities stemming from a vast network of practitioners and thinkers – thus providing a tentative answer to the question posed by the Biennale curator Hashim Sarkis: How will we live together?

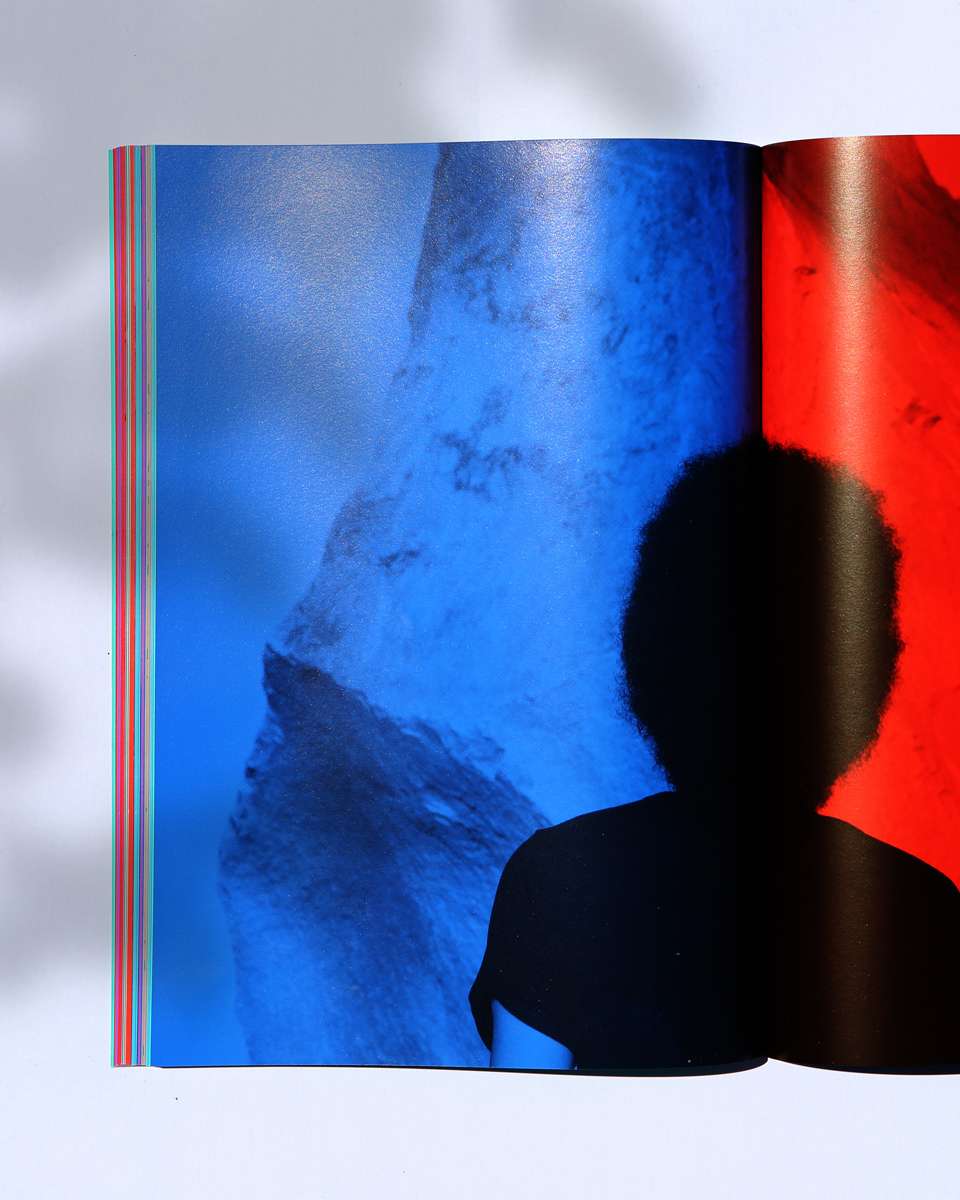

The book you are holding in your hands, entitled Voices (Towards Other Institutions), represents the final act of the coral, multiform, articulated, two-year-long experiment carried out by the curatorial team.

It gathers twenty-eight texts released weekly between May 2020 and May 2021 on pavilionrus.com commissioned from an interdisciplinary cohort of practitioners and thinkers, from Russia and beyond, in an attempt to mobilise a peaceful yet vocal army of engaged individuals, and a diverse poll of perspectives and sensitivities and dissent against the existing modes of institutional functioning.

Each voice is based on a reconsideration of traditional institutional models, and brings an original perspective into alternative forms of constituencies and collectiveness – either by challenging the cultural status quo or by searching for emphatic and meaningful forms of alliance and kinship.

Voices as an editorial project grew out of a trouble time, in which the outbreak of Covid-19 exacerbated the flaws of existing cultural and institutional models, brought to the fore new and old forms of violence, exposed the limits of transnational models of governance, and made visible the short-sightedness of the dominant neoliberal paradigm. Inevitably then, the criticality of the current historical moment provides the background against which the majority of the contributors had to work to develop their thoughts around alternative ways of thinking and doing cultural institutions.

Some authors addressed the topic from a speculative standpoint, focusing on the way in which language constructs our reality; others instead looked nostalgically at the political might and the specific type of body-based knowledge that arise from the experience of sharing a physical environment – be it a kitchen, a school classroom or an underground club. Some employed the language of intimacy to write about their experience of isolation and alienation in a context of time suspension, reclaiming the value of empathy as a compelling tool in the face of existing world order and labour exploitation.

Others embraced their roles as public figures (museum directors, school deans, etc.) to challenge the functioning and the mechanics of the cultural institutions they represent. Some lamented the depletion of natural resources, and the parallel exhaustion of human bodies – especially of those who are poor, deprived of any power and displaced. Finally, some discussed forms of abuse that pass through data sovereignty and technological bias. Others focused on the social potential of digital gaming environments, alluding to the online transition of the Russian Pavilion itself.

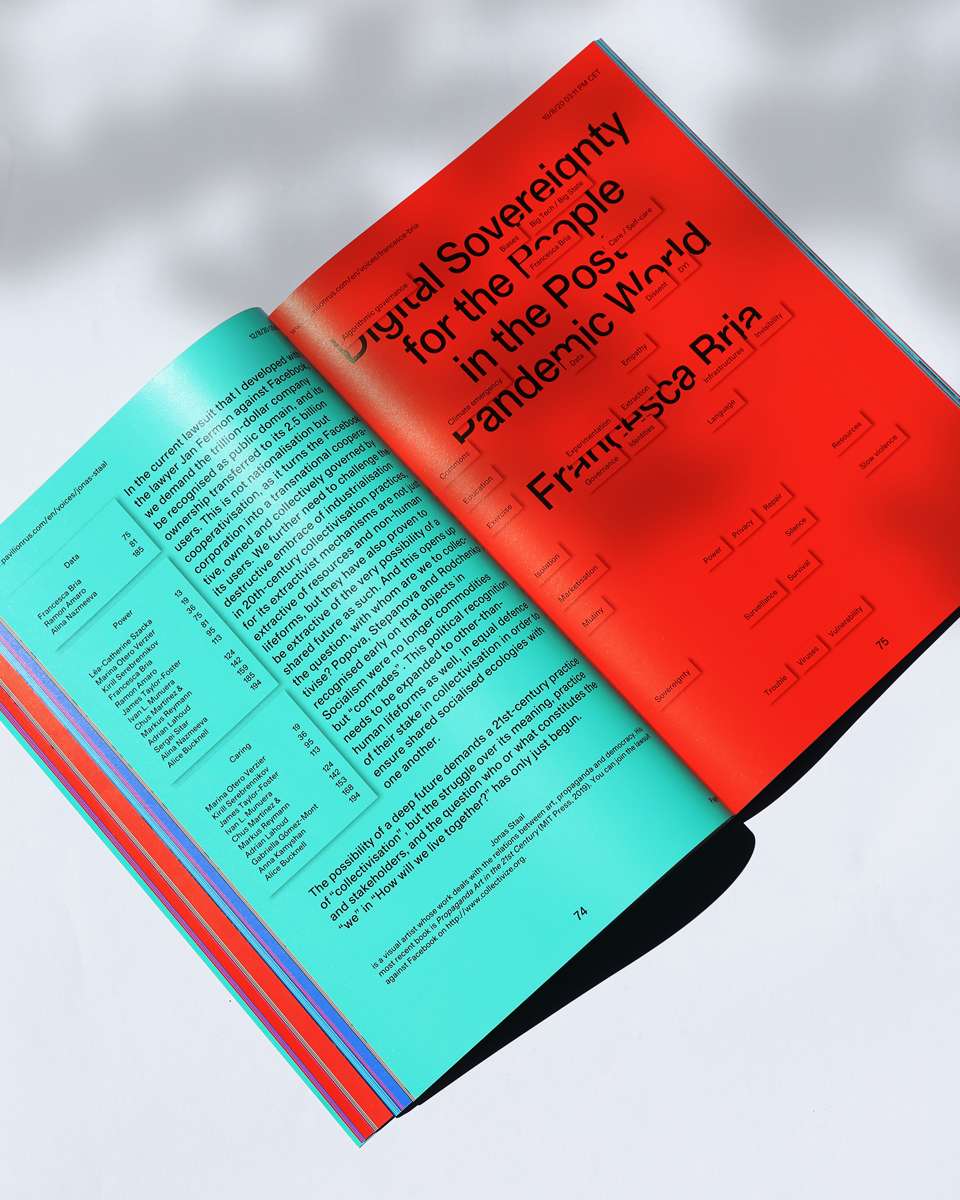

Within this multiplicity of angles, the book as a whole works almost as a polyphonic piece in the making, showcasing a web of unexpected connections across different thematic clusters. Voices here are gathered into a single volume and according to a seemingly random structure. In balance between a traditional publication and a website, texts are not organised into chapters but associated with a glossary of ten keywords which, just like hashtags, trace connections across various contributions and re-assemble them into a multiplicity of possible indexes.

The ten keywords highlighted in this introduction are further explored by ten semantic landscapes, each one functioning as a “navigational tool” across the texts and setting a more specific stage to each individual contribution. Voices (Towards Other Institutions) was not conceived as an academic publication but rather as an accessible tool in the hands of a broad and diverse readership. Stemming from the belief that an alternative way of thinking and doing in cultural institutions does exist, its ambition is to inspire and provoke. In its attempt to challenge the present, it positions itself as a tool to re-imagine the future.

Edited by 2050.plus /

Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli and Erica Petrillo

With texts by

Ramon Amaro, Sepake Angiama, Paola Antonelli, Alessandro Bava, Daniel Blanga Gubbay, Giovanna Borasi, Francesca Bria, Alice Bucknell, Konstantin Budarin, Ilya Budraitskis, Elise By Olsen, Gabriella Gómez-Mont, Anna Kamyshan, Adrian Lahoud, Beatrice Leanza, Chus Martínes & Markus Reymann, Timothy Morton, Ivan L. Munuera, Alina Nazmeeva, Marina Otero Verzier, Kirill Serebrennikov, Sergei Sitar, Jonas Staal, Jenna Sutela, Léa-Catherine Szacka, Pelin Tan, James Taylor-Foster, Oxana Timofeeva

Designed by Lorenzo Mason Studio /

Lorenzo Mason, Dafne Pagura, Simone Spinazzè